Cult VIP: Mike Kuchar

The lurid homoerotic comics of one half of 1950s underground cinema's visionary twins

Gatherings happened in lofts, apartments or unused shops. But the particular loft apartment of experimental filmmaker and New York tastemaker Ken Jacobs was the place to be. “Yeah, he enjoyed our pictures and said, ‘Come back next month,’ and invited Jonas Mekas, who had a column in The Village Voice. (Mekas) also liked our pictures and wrote a big raving review. It was a great time to be making pictures; we knew Andy Warhol, Jack Smith, Kenneth Anger, Allen Ginsberg, they’d all come to our shows and say ‘hi’. It was a very exciting time. It was a real exchange. Everyone worked separately, everyone had their own vision, but we’d all meet up at the premieres.”

Mekas, now considered a godfather of avant-garde cinema, remembers what he thought when he first saw their work: “These two kids from the Bronx arrived on the New York film underground scene with a bang. The 8mm film camera, relegated to filming honeymoon trips or first steps of babies, was almost overnight changed into a means of creating these huge neo-Hollywood pop spectaculars. And even more incredible: they did it in their kitchen!”

But the passionate, human colour-dramas made by the Kuchars during this period were very different to the formal, avant-garde approach of their contemporaries. “They were minimal,” Mike says, explaining the difference between the styles. “They aimed a camera at a crack in the wall for like, a half hour. Maybe there would be a slight light-change. We just did what was natural to us, what felt right. Our films were a regurgitation of the pop culture we are all submerged in. We were beginning to see a certain appreciation for ‘camp’. For me ‘camp’ means that you set up your tent on some established recreation ground – in this case Hollywood – and you have a little fun with it. It’s about taking the language of movies and making it so overblown it’s glorious.”

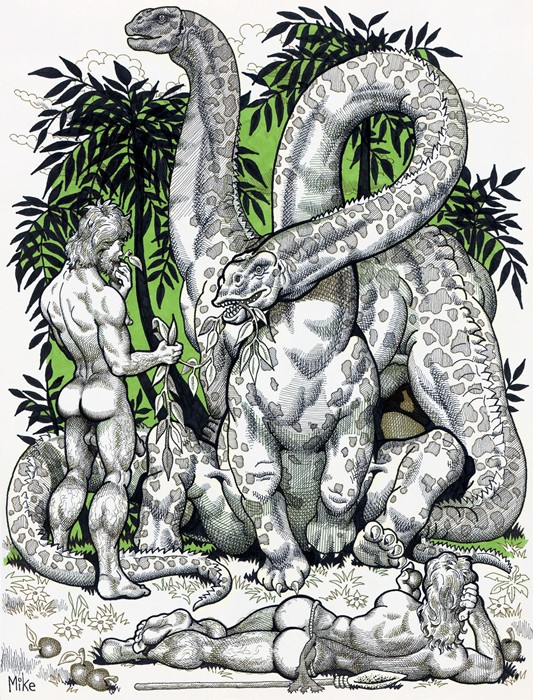

Most recently, Mike’s artistic vision has infiltrated the world of underground comics. Some of his homoerotic illustrations have taken 20 years to emerge, but are now being shown, most notably at last year’s Frieze London. The majority of his new artworks apply the same camp sensibility of his films to still images of muscular men, dinosaurs and neolithic imagery. There’s a direct link between the Kuchars and the American underground comic scene. “We were all friends!” Mike says. “Art (Spiegelman) lived next door to my brother for a few years.” It was natural that Mike moved towards comics, and like all his projects, it started in a typically Kucharian manner. “So I got recommended by a friend to submit for this underground comic-book called Gay Heart Throbs. It did very well – I drew it better and knew the subject better than the other guys. Other editors saw it and got in touch, so I started making more and that got me back into drawing.”

Mike’s illustrations and films are thematically connected. “I never can separate one from another,” Losier says. “If you look at Mike’s muscular drawings of men with giant penises in fairytale landscapes, surrounded by peace and joy, pleasure, you’ll find the same in his films!” Sam Ashby, editor of queer film-zine Little Joe, says, “I would say the form of comic-making allows his more unattainable sexual fantasies to exist, while the films exhibit a more poetic longing, often exploring forms of male portraiture that diverge significantly from the comics while retaining something uniquely ‘Mike’ about them.”

Mike has now picked up where his brother left off at the San Francisco Art Institute, teaching George’s famed Electrographic Sinema course and passing on this poetic, low-budget and gloriously gaudy tradition of filmmaking. In a way the circle completes itself, as a new generation of film students are forced from their comfort zones and challenged to create frenzied, budget-less, DIY movies in the manner that the Kuchar brothers started out. And Mike Kuchar’s influence is global. As Ben Rivers, the experimental English filmmaker behind Two Years At Sea (2011), explains, “There’s absolutely no doubt about it, the Kuchar brothers helped me down the path I now walk. Their films were the first experimental films I saw, and in a flash I knew that there were no limits to what could be done! I eventually met Mike Kuchar in the 90s – he’d just shown Sins of the Fleshapoids – and already being a massive fan, I was blown away by seeing this film for the first time on the big screen. I accosted him in the aisle and he gave me his address on a piece of paper which I still have in a frame.”

“The way I see it, movies had always been made about crazy people. When we came along you had the crazy people making the goddamn movies. So you got the real stuff.

While not as famous as such peers as Warhol and Anger, Mike Kuchar’s work captured the poetic traits of filmmaking in their earliest and purest form. His pictures are unabashed, uniquely his own and an entirely captivating part of a seminal time and place in 20th-century art. But Mike is in every way a gentle giant, never wanting to boast or overstate his importance. “The way I see it now, movies had always been made about crazy people,” he says. “When we came along you had the crazy people making the goddamn movies. So you got the real stuff. But it was always fun. Me and my brother, we kept up that tradition. John Waters hates it when I call it a hobby and he’s got a point. I guess I could call it a vocation, a way of speaking, a way of coming to terms with existence. But when we were young it was all about having fun, and it’s still that way now.”